Sets and Set Comprehensions

Python Sets Set Comprehensions

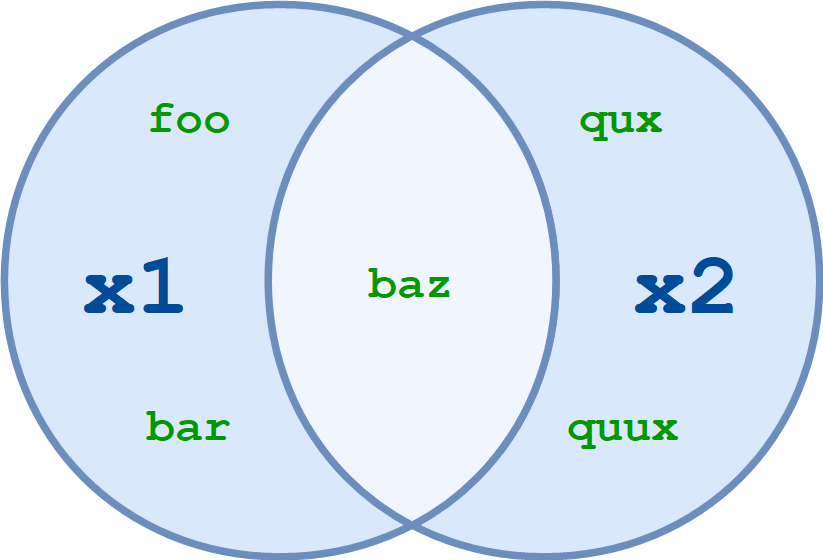

Perhaps you recall learning about sets and set theory at some point in your mathematical education. Maybe you even remember Venn diagrams:

In mathematics, a rigorous definition of a set can be abstract and difficult to grasp. Practically though, a set can be thought of simply as a well-defined collection of distinct objects, typically called elements or members.

Grouping objects into a set can be useful in programming as well, and Python provides a built-in set type to do so. Sets are distinguished from other object types by the unique operations that can be performed on them.

Here’s what you’ll learn in this tutorial:

- You’ll see how to define set objects in Python and discover the operations that they support.

- You’ll also learn about frozen sets, which are similar to sets except for one important detail.

Defining a Set

Python’s built-in set type has the following characteristics:

- Sets are unordered.

- Set elements are unique. Duplicate elements are not allowed.

- A set itself may be modified, but the elements contained in the set must be of an immutable type.

A set can be created in two ways. First, you can define a set with the built-in set() function:

x = set(<iter>)

x = set(['foo', 'bar', 'baz', 'foo', 'qux'])

print(x)

{'foo', 'baz', 'bar', 'qux'}

y = set(('foo', 'bar', 'baz', 'foo', 'qux'))

print(y)

{'foo', 'baz', 'bar', 'qux'}

z = set()

print(type(z), z)

<class 'set'> set()

Strings are also iterable, so a string can be passed to set() as well. You have already seen that list(s) generates a list of the characters in the string s. Similarly, set(s) generates a set of the characters in s:

s = 'data focused python'

print(s)

data focused python

for c in s:

print(c)

d

a

t

a

f

o

c

u

s

e

d

p

y

t

h

o

n

print(list(s))

['d', 'a', 't', 'a', ' ', 'f', 'o', 'c', 'u', 's', 'e', 'd', ' ', 'p', 'y', 't', 'h', 'o', 'n']

print(set(s))

{'e', 'f', 'o', 'u', 'd', 'a', 's', 'n', 't', 'c', 'p', 'y', 'h', ' '}

s = 'data focused python is cool because we learn python and work with data'

words = s.split(' ')

print(words)

print(set(words))

['data', 'focused', 'python', 'is', 'cool', 'because', 'we', 'learn', 'python', 'and', 'work', 'with', 'data']

{'because', 'python', 'with', 'work', 'is', 'and', 'learn', 'we', 'focused', 'data', 'cool'}

You can see that the resulting sets are unordered: the original order, as specified in the definition, is not necessarily preserved. Additionally, duplicate values are only represented in the set once, as with the string ‘foo’ in the first two examples and the letter ‘u’ in the third.

Alternately, a set can be defined with curly braces ({}):

x = {<obj>, <obj>, ..., <obj>}

When a set is defined this way, each

Thus, the sets shown above can also be defined like this:

x = { 'foo', 'bar', 'baz', 'foo', 'qux' }

print(type(x), x)

<class 'set'> {'foo', 'baz', 'bar', 'qux'}

y = {'q', 'u', 'u', 'x'}

print(type(y), y)

<class 'set'> {'x', 'q', 'u'}

To recap:

- The argument to set() is an iterable. It generates a list of elements to be placed into the set.

- The objects in curly braces are placed into the set intact, even if they are iterable.

Observe the difference between these two set definitions:

x = {'foo'}

print(type(x), x)

<class 'set'> {'foo'}

y = set('foo')

print(type(y), y)

<class 'set'> {'f', 'o'}

A set can be empty. However, recall that Python interprets empty curly braces ({}) as an empty dictionary, so the only way to define an empty set is with the set() function:

x = {}

print(type(x))

<class 'dict'>

y = set()

print(type(y))

<class 'set'>

An empty set is falsy in Boolean context:

x = set()

bool(x)

False

x or 1

1

x and 1

set()

You might think the most intuitive sets would contain similar objects—for example, even numbers or surnames:

s1 = {2, 4, 6, 8, 10}

s2 = {'Smith', 'McArthur', 'Wilson', 'Johansson'}

Python does not require this, though. The elements in a set can be objects of different types:

x = {42, 'foo', 3.14159, None}

print(x)

{'foo', 42, 3.14159, None}

Don’t forget that set elements must be immutable. For example, a tuple may be included in a set:

x = {42, 'foo', (1, 2, 3), 3.14159}

print(x)

{'foo', 42, (1, 2, 3), 3.14159}

But lists and dictionaries are mutable, so they can’t be set elements:

a = [1, 2, 3]

x = {a}

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

/var/folders/jd/pq0swyt521jb2424d6fvth840000gn/T/ipykernel_22205/1659420868.py in <module>

1 a = [1, 2, 3]

----> 2 x = {a}

TypeError: unhashable type: 'list'

Set Size and Membership

x = {'foo', 'bar', 'baz'}

len(x)

3

'bar' in x

True

'qux' in x

False

Operating on a Set

Many of the operations that can be used for Python’s other composite data types don’t make sense for sets. For example, sets can’t be indexed or sliced. However, Python provides a whole host of operations on set objects that generally mimic the operations that are defined for mathematical sets.

Operators vs. Methods

Most, though not quite all, set operations in Python can be performed in two different ways: by operator or by method. Let’s take a look at how these operators and methods work, using set union as an example.

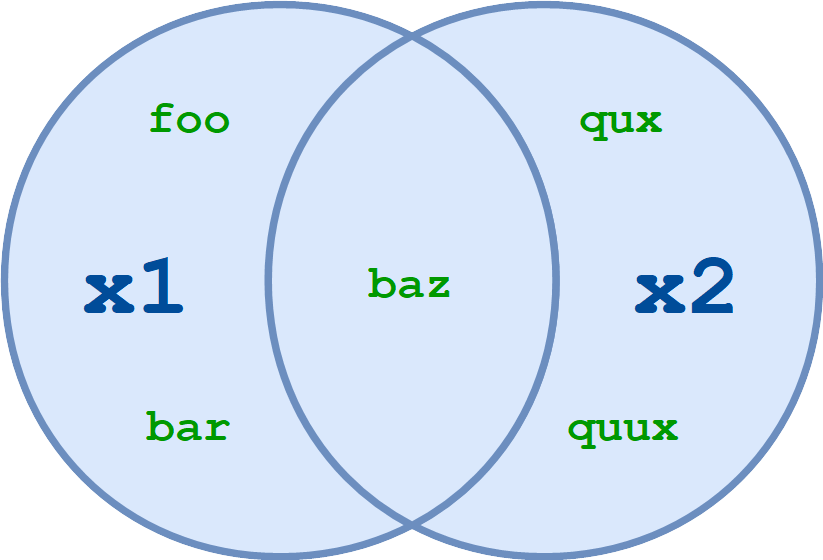

Given two sets, x1 and x2, the union of x1 and x2 is a set consisting of all elements in either set.

Consider these two sets:

x1 = {'foo', 'bar', 'baz'}

x2 = {'baz', 'qux', 'quux'}

The union of x1 and x2 is {'foo', 'bar', 'baz', 'qux', 'quux'}.

In Python, set union can be performed with the | operator:

union_x = x1 | x2

print(union_x)

{'foo', 'quux', 'baz', 'bar', 'qux'}

# note : there aren't any duplicates

print(len(union_x), len(x1), len(x2))

5 3 3

Set union can also be obtained with the .union() method. The method is invoked on one of the sets, and the other is passed as an argument:

x1.union(x2)

{'bar', 'baz', 'foo', 'quux', 'qux'}

| The way they are used in the examples above, the operator and method behave identically. But there is a subtle difference between them. When you use the | operator, both operands must be sets. The .union() method, on the other hand, will take any iterable as an argument, convert it to a set, and then perform the union. |

Observe the difference between these two statements:

x1 | ('baz', 'qux', 'quux')

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

/var/folders/jd/pq0swyt521jb2424d6fvth840000gn/T/ipykernel_22205/1141666621.py in <module>

----> 1 x1 | ('baz', 'qux', 'quux')

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for |: 'set' and 'tuple'

x1.union(('baz', 'qux', 'quux'))

{'bar', 'baz', 'foo', 'quux', 'qux'}

Available Operators and Methods

Below is a list of the set operations available in Python. Some are performed by operator, some by method, and some by both. The principle outlined above generally applies: where a set is expected, methods will typically accept any iterable as an argument, but operators require actual sets as operands.

Union

x1 = {'foo', 'bar', 'baz'}

x2 = {'baz', 'qux', 'quux'}

print(x1.union(x2))

print(x1 | x2)

{'foo', 'quux', 'baz', 'bar', 'qux'}

{'foo', 'quux', 'baz', 'bar', 'qux'}

More than two sets may be specified with either the operator or the method:

a = {1, 2, 3, 4}

b = {2, 3, 4, 5}

c = {3, 4, 5, 6}

d = {4, 5, 6, 7}

print(a.union(b, c, d))

print(a | b | c | d)

{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7}

{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7}

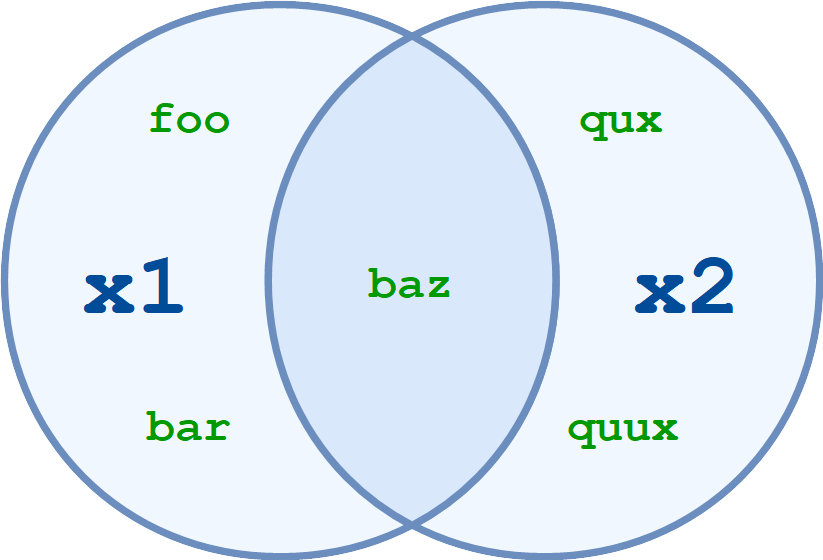

Intersection

x1 = {'foo', 'bar', 'baz'}

x2 = {'baz', 'qux', 'quux'}

print(x1.intersection(x2))

print(x1 & x2)

{'baz'}

{'baz'}

You can specify multiple sets with the intersection method and operator, just like you can with set union:

a = {1, 2, 3, 4}

b = {2, 3, 4, 5}

c = {3, 4, 5, 6}

d = {4, 5, 6, 7}

print(a.intersection(b, c, d))

print(a & b & c & d)

{4}

{4}

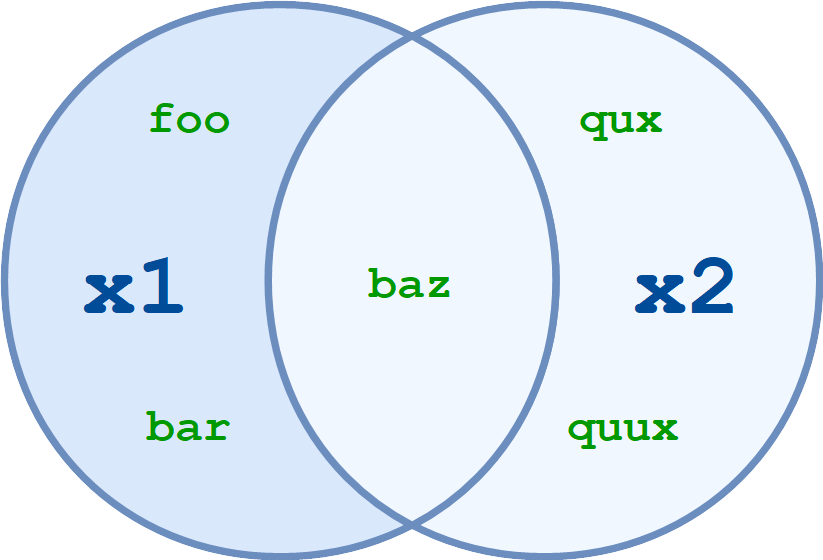

Difference

x1 = {'foo', 'bar', 'baz'}

x2 = {'baz', 'qux', 'quux'}

print(x1.difference(x2))

print(x1 - x2)

{'foo', 'bar'}

{'foo', 'bar'}

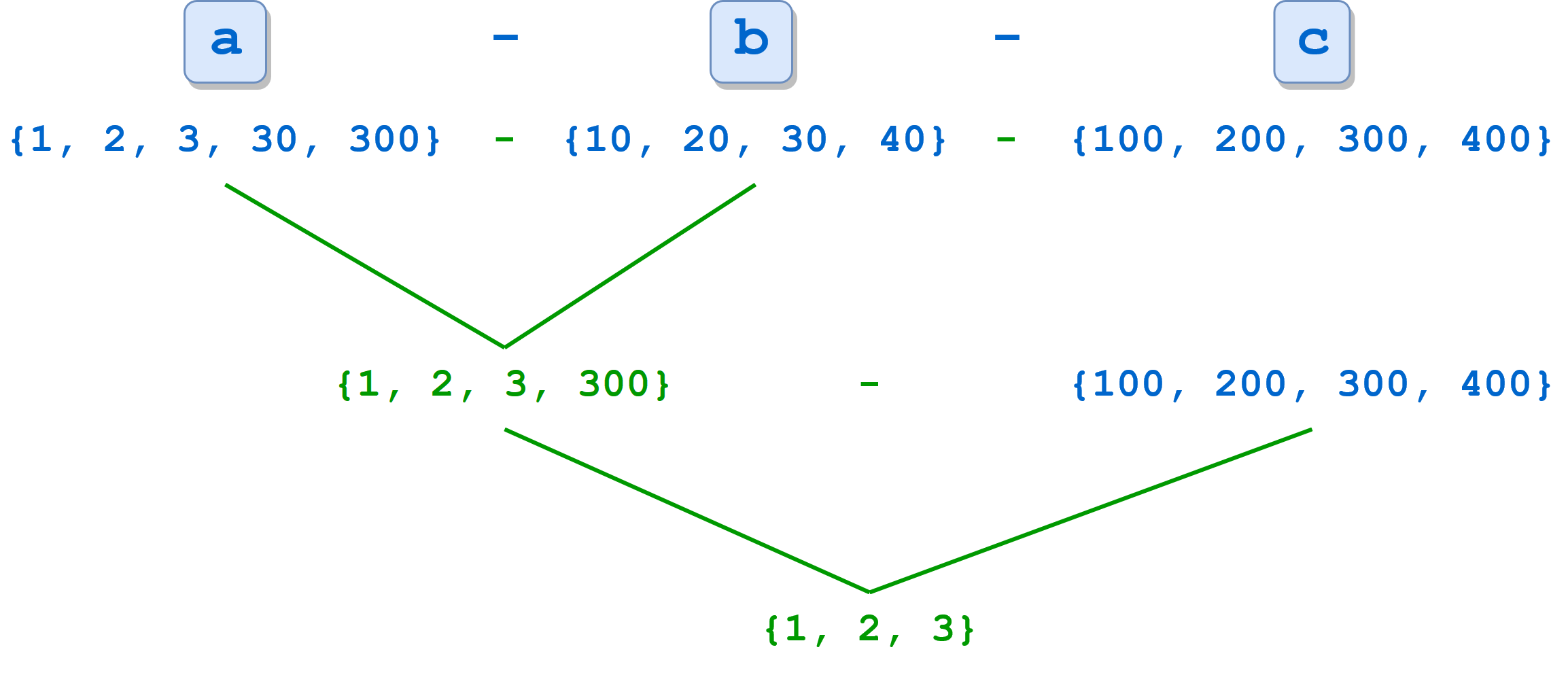

Once again, you can specify more than two sets:

a = {1, 2, 3, 30, 300}

b = {10, 20, 30, 40}

c = {100, 200, 300, 400}

print(a.difference(b, c))

print(a - b - c)

{1, 2, 3}

{1, 2, 3}

When multiple sets are specified, the operation is performed from left to right. In the example above, a - b is computed first, resulting in {1, 2, 3, 300}. Then c is subtracted from that set, leaving {1, 2, 3}:

Symmetric Difference

x1 = {'foo', 'bar', 'baz'}

x2 = {'baz', 'qux', 'quux'}

print(x1.symmetric_difference(x2))

print(x1 ^ x2)

{'bar', 'qux', 'foo', 'quux'}

{'bar', 'qux', 'foo', 'quux'}

The ^ operator also allows more than two sets:

a = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

b = {10, 2, 3, 4, 50}

c = {1, 50, 100}

print(a ^ b ^ c)

{100, 5, 10}

Disjoint

Determines whether or not two sets have any elements in common.

x1.isdisjoint(x2) returns True if x1 and x2 have no elements in common:

x1 = {'foo', 'bar', 'baz'}

x2 = {'baz', 'qux', 'quux'}

print(x1.isdisjoint(x2))

False

x3 = x2 - {'baz'}

print(x1.isdisjoint(x3))

True

If x1.isdisjoint(x2) is True, then x1 & x2 is the empty set:

x1 = {1, 3, 5}

x2 = {2, 4, 6}

print(x1.isdisjoint(x2))

True

print(x1 & x2)

set()

Is Subset

Determine whether one set is a subset of the other.

In set theory, a set x1 is considered a subset of another set x2 if every element of x1 is in x2.

x1.issubset(x2) and x1 <= x2 return True if x1 is a subset of x2:

x1 = {'foo', 'bar', 'baz'}

print(x1.issubset({'foo', 'bar', 'baz', 'qux', 'quux'}))

True

x2 = {'baz', 'qux', 'quux'}

print(x1 <= x2)

False

Is Proper Subset

A proper subset is the same as a subset, except that the sets can’t be identical. A set x1 is considered a proper subset of another set x2 if every element of x1 is in x2, and x1 and x2 are not equal.

x1 = {'foo', 'bar'}

x2 = {'foo', 'bar', 'baz'}

print(x1 < x2)

True

x1 = {'foo', 'bar', 'baz'}

x2 = {'foo', 'bar', 'baz'}

print(x1 < x2)

False

Is Superset

A superset is the reverse of a subset. A set x1 is considered a superset of another set x2 if x1 contains every element of x2.

x1.issuperset(x2) and x1 >= x2 return True if x1 is a superset of x2:

x1 = {'foo', 'bar', 'baz'}

print(x1.issuperset({'foo', 'bar'}))

True

x2 = {'baz', 'qux', 'quux'}

print(x1 >= x2)

False

Is Proper Superset

A proper superset is the same as a superset, except that the sets can’t be identical. A set x1 is considered a proper superset of another set x2 if x1 contains every element of x2, and x1 and x2 are not equal.

x1 = {'foo', 'bar', 'baz'}

x2 = {'foo', 'bar'}

print(x1 > x2)

True

x1 = {'foo', 'bar', 'baz'}

x2 = {'foo', 'bar', 'baz'}

print(x1 > x2)

False

Frozen Sets

Python provides another built-in type called a frozenset, which is in all respects exactly like a set, except that a frozenset is immutable. You can perform non-modifying operations on a frozenset:

x = frozenset(['foo', 'bar', 'baz'])

print(x)

frozenset({'foo', 'baz', 'bar'})

print(len(x))

3

print(x & {'baz', 'qux', 'quux'})

frozenset({'baz'})

But methods that attempt to modify a frozenset fail:

x.add('quux')

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

AttributeError Traceback (most recent call last)

/var/folders/jd/pq0swyt521jb2424d6fvth840000gn/T/ipykernel_22205/3158252394.py in <module>

----> 1 x.add('quux')

AttributeError: 'frozenset' object has no attribute 'add'

Set Comprehension

import random

from random import randint

seed = 1234

random.seed(seed)

x = 0

y = 5

a = [randint(x, y) for i in range(0, 10)]

print(a)

[3, 0, 0, 0, 4, 0, 5, 5, 0, 0]

random.seed(seed)

x = 0

y = 5

b = {randint(x, y) for i in range(0, 10)}

print(b)

{0, 3, 4, 5}

random.seed(seed)

a = ['Even' if i % 2 else 'Odd' for i in range(10)]

print(a)

['Odd', 'Even', 'Odd', 'Even', 'Odd', 'Even', 'Odd', 'Even', 'Odd', 'Even']

random.seed(seed)

b = {'Even' if i % 2 else 'Odd' for i in range(10)}

print(b)

{'Odd', 'Even'}